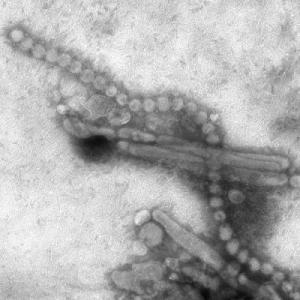

UPDATE ON THE NEW BIRD FLU: HOW DANGEROUS TO PEOPLE? Does H7N9, the new avian influenza A virus that surfaced in March, have the potential for worldwide mischief? Who knows? WHO knows, or says it does. The World Health Organization declares H7N9 to be a serious threat and reports that there have been 128 lab-confirmed cases and 27 deaths, all in China.

As yet there is no established evidence of human-to-human transmission. Reservoirs of the H7N9 bird flu virus are still unknown because it doesn't seem to cause symptoms in birds. Chickens continue to be the leading suspect.

Kate Yandell has a useful overview of present and future lab work on H7N9 at The Scientist. Susan Young summarizes recent journal articles on H7N9 at Tech Review. Meanwhile, Declan Butler and David Cyranoski report at Nature News on a flap over whether Chinese scientists were being robbed of credit for the H7N9 sequences they uploaded to the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID) database on the day the virus was first reported in March.

For a graphical overview, there's a lovely Venn diagram at Geeks are Sexy illustrating the various kinds of flu and which animal species each one infects.

At the Health Care Blog, doc Colin Son is irritated by the degree of alarmism that infects public discussions about the dangers of infectious disease like H7N9 and antibiotic-resistant bugs. They are not nearly so risky for health as heart or lung disease, and yet accounts of infectious disease provoke much more hand-wringing and near-panic. He blames the media, of course, but also medical authorities like WHO, for spreading unneccesary alarm.

I think he's right that we tend to be much more panicky about infectious diseases, even ones like the new bird flu where we don't yet know whether alarm is warranted. I wonder, though, whether those fears are entirely a product of media attempts to capture eyeballs and official medical alarmism. My hunch is that it also has something to do with human brain organization. We are primed to watch out for immediate threats, but our attention spans are brief. Long-term threats dribble off the radar screen — especially if avoiding them involves giving up pleasures like whipped cream and cigarettes and SUVs.

Maryn McKenna, the journalistic authority on antibiotic resistance in particular and infectious disease in general, a month ago listed several sources of flu information she regards as trustworthy on her blog Superbug. She also handed out sensible advice on how to read the news about H7N9 (and, by implication, other such looming crises).

Don’t assume that everyone who is loading information onto their blogs or pushing it onto Twitter is doing it in a sharing spirit of helpfulness. There are people — you can see this already — who are opportunistically using this to feed their egos, angle for jobs, or generally to stir up trouble. More than ever, it’s important to be skeptical about the sources of the information you consume.

HOW BAD WAS SEASONAL FLU IN THE U.S? The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has decided that the 2012-2013 seasonal flu in the U.S. is winding down. In January I promised you an update on the severity of this year's seasonal flu because I wanted to know who was right: virus expert Vincent Racaniello (who predicted that flu wouldn't be a big deal this year) or the io9 blogger whose prognosis was that it would be "terrifying."

As is so often the case in this world, both forecasts turned out to be extreme. io9 was unduly alarmist and Racaniello wasn't alarmist enough. The CDC says the flu season started early, was "intense," and lasted a bit longer than usual. It was comparable to the 2003-2004 and 2007-2008 influenza seasons, which have been called “moderately severe.”

Effectiveness of the year's flu vaccine wasn't impressive, but CDC's faith in flu vaccines remains bullish, particularly for those over 65. This year that age group accounted for half of all hospitalizations for flu.

REMEMBER THE NEW CORONAVIRUS? That mysterious new SARS-like coronavirus we talked about here in March is still with us. The case count is now 24, including 16 deaths mostly in the Middle East. Saudi Arabia has just disclosed 7 new cases and 5 deaths. WHO and other medical authorities are not happy about Saudi Arabia's record of not coming clean about these cases, Helen Branswell reports at Canadian Press.

Branswell tweeted "Fascinating that #China is being more transparent about #H7N9 than #Saudi Arabia is about #coronavirus." At Superbug, McKenna composes a chronology of Saudi Arabia's disclosures (or lack thereof) and compares that country unfavorably with how China seems to be handling H7N9 information.

These are trenchant comments, considering that China's bad record of coming clean about the original SARS virus has made people unsure about trusting what China is saying about H7N9. Alexander Abad-Santos, for instance, views with deep suspicion the Chinese Center of Disease Control's recent decision to stop publishing its H7N9 data in English.

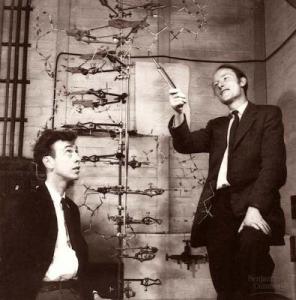

FUN WITH DNA Owing partly to the press of other recent events like the Boston Marathon bombing, I blew past the various anniversaries of DNA and will now catch up a bit. The Watson-Crick structure paper was published 60 years ago, on April 25, and the 10th anniversary of the first time the Human Genome Project was completed took place April 14.

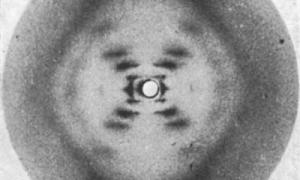

Cambridge celebrated its most famous researchers with a tribute to Francis Crick, who died in 2004. It was livestreamed April 25 and video replays of the talks are here. At his newish Discover blog Fire in the Mind, George Johnson describes why Rosalind Franklin took such a long time to realize that her matchless X-ray crystallography of DNA, which put Watson and Crick on the right road to how DNA was built, was showing a helical structure.

But this is Fun with DNA, so what I really want to tell you about is two Guardian posts. First, by Adam Rutherford, is a diatribe against depictions of DNA as a left-twisting molecule. It twists to the right, dammit. Rutherford is in despair about how hard it is to get people to do the right thing. Sinister DNA is everywhere, he says: illustrating a podcast he did with Guardian science editor Alok Jha, defacing a review of his latest book, Creation, that ran in the Observer, and even appearing on the cover of Nature.

More than once left-twisting DNA serves as ironic commentary, unconscious though it may be. It appears, for example, on the cover of a Harvard University Press book titled Genetic Explanations: Sense and Nonsense. See for yourself.

Mark Lorch's DNA tribute consists of showing us how to construct a model of DNA not unlike the one Watson and Crick put together in the photo above. Only this DNA model is made from licorice whips and jelly babies.

Jelly babies are a Brit sweetie, but any watcher of Doctor Who will be familiar with them. It's possible these somewhat macabre candies are available in the US too, but Lorch says you can use marshmallows instead. You'd need the miniatures, I should think, unless you want your model to be as big as Watson and Crick's. Doesn't look difficult at all, but might be a little sticky.

As a bonus, Lorch's post also contains instructions for extracting DNA from a kiwi. The fruit, not the bird.

.png)