Happy #NASW90th, everyone! The year 2024 marks the 90th anniversary of the founding of our National Association of Science Writers — and NASW members are sharing their stories and memories in celebration.

Read on below for the contributions so far from NASW members — then contribute your own words to our NASW 90th Anniversary Story + Photo Share project! Memories from your first NASW gathering? Friendships and mentors you gained through NASW? Moments in history where science writing made a difference? Your hopes for science writing in the next 90 years? We'd also love photos of NASW gatherings or photos of yourself on the job, in the field or at your desk. Help us commemorate this moment in NASW's history.

Stories have been edited for clarity and layout purposes. Follow more #NASW90th celebrations on Bluesky and on LinkedIn.

Early Support

"Attached is the I.D. photo I chose for my first NASW membership card, when I signed up in summer 2023 after college graduation. In between then and winter 2024 — when I landed my first full-time job out of college — NASW gave me lots of support. Its 2023 virtual convention allowed me to meet countless new peers and mentors in the field, who were all very happy to give me advice on networking and job searching. And now I work at a science publishing company!" — Ariel Finkle (NASW member since 2023)

With the Tides

"Earlier this year, 2024, during a time of financial hardship, I was able to renew my membership for free. I resolved to take advantage of all NASW has to offer, and to be its biggest cheerleader... I am really grateful to NASW for helping me upskill in my journalism endeavors and, in a time when the economy is still unstable, provides free resources for me to become an even better writer. The best part is that my financial situation is slowly improving, and I have learned new skills — and I look forward to giving back to NASW and helping people learn about ways they can use NASW to stay connected to the science writing world, now that I am past that bleak economic time." — Sheeva Azma (NASW member since 2020)

Glory Days

No one has cut their teeth on science writing at a better time than I, in the 1960’s, when science fiction was becoming fact, seemingly by the day. Watson and Crick had received the Nobel Prize for their DNA work. Quasars had astronomers agog. Astronauts were booming into space. The word processor and laser arrived. And newspapers were in their Cretaceous Period, flourishing but on the brink of apocalypse. In 1959, I started as a copy boy at the New York Daily Mirror, running lunches and stripping the racing wires; if I could fight my way through reporters clustered around the wire machines, hoping their horses had come in. In those days, big-city street reporters were largely a blue-collar bunch, working and playing hard. I made my way through weeklies, driving the truck that delivered papers overnight for one, and finally landed at a daily, The Bergen Evening Record in Hackensack, N.J.

There I successfully begged my editors to let me cover my two main interests, law enforcement/crime and science. I landed assignments such as interviewing mob boss Tommy Eboli sitting with his family at his kitchen table; and reporting on research by the many big pharma companies in the coverage area. Best of all, I was able to tie both interests together covering a major case of industrial espionage targeting drug companies.

My big break came when the spanking-new Council for the Advancement of Science writing assigned me a mentor, [former NASW president and inaugural CASW president] Earl Ubell, then of the New York Herald Tribune, later WCBS-TV (where I later ended up as “The Animal Man” on a kid’s program; that’s another story). I have spent the rest of my life in fruitless quest to write science with the flair and skill that Ubell possessed. The CASW program propelled me into a Sloan-Rockefeller Fellowship at Columbia and I was off to the races. I was an editor in the science division of Scholastic Magazines and then Curator of Publications for the New York Zoological Society at the Bronx Zoo (now called the Wildlife Conservation Society). In 1971, I left my office with a fireplace at the Bronx Zoo and went full time freelance. Again I was able to meld my two interests, becoming versed in covering international wildlife crime. Early on, though I forget exactly when, I joined NASW. If my memory is correct, I took a brief hiatus, and then rejoined. Attending meetings as a newbie thrust me into the science writing universe — invaluable.

I am turning 86, so may wax nostalgic, but I am convinced I reported and wrote in the shadow of science writing giants. Besides Ubell, I rubbed elbows with Walter (of the We Are Not Alone fame) Sullivan of The New York Times and [former NASW president] Alton Blakeslee of the Associated Press. I do not think we will see their like again. They were all old-school journalists who turned to science writing when science news grabbed banner headlines.

Each of them had his own approach to handling science. I remember Sullivan and Ubell writing about the same time on quasars. Sullivan’s lead was informative but technical, suited to an informed audience. Perhaps reflecting the difference between the Gray Lady and the Trib, Ubell began (and I hope I am remembering it exactly): “A fire burns on the fringes of the universe.” Almost every time I strive to make science interesting, those words emerge from the past and form in my mind. — Ed Ricciuti (NASW member since 1960's)

A Room Full of Storytellers

I joined NASW in 2008, but didn't attend my first ScienceWriters meeting until 2010, when it was held in New Haven, Conn. I can remember walking into the opening night reception and being overwhelmed. I found it incredibly intimidating — a sea of unfamiliar faces, interspersed every so often by faces I knew only from their byline photos. But I had spent a decade as a reporter before becoming a PIO, and if there is one thing reporters (even former reporters) are good at, it is walking up to people you don't know and asking them questions. So that's what I did.

It quickly became clear that I had found my community. The people in that room came from many different backgrounds, but there were certain common threads that tied them all together. This was a group of people who was interested in how things work and why they work that way. Everyone thought it was important to help people gain a deeper understanding of the world around us. Everyone agreed that journalism was not only valuable but important. That may all sound a little high-minded, but what it boiled down to was that this was a group of people who were not boring. The conversations were fascinating. This was a room full of storytellers. This was fun.

Over the course of that meeting it also became clear that these were people who took science writing seriously. They wanted to get better at their craft. They wanted to get better at finding story ideas. At finding the right people to talk to. At writing. At editing. At everything. These were people who wanted to keep learning and growing. They were also people who were willing to share what they knew, so that others could also learn and grow. How great is that?

Over time many of those unfamiliar faces became acquaintances, then friends. Making my membership in NASW not only professionally valuable, but personally rewarding.

I've learned a lot from the various sessions and panels I've attended through NASW — whether in person or online. And I've learned even more through conversations I've had with people I met through NASW. I certainly wouldn't be the science writer I am without NASW, for whatever that's worth. And I wouldn't be the person I am without the relationships I've made there. And that is worth a great deal. — Matt Shipman (NASW member since 2008)

Rescue Mission

Checking my membership card, I see that I joined NASW in 1987. I had been a member of New England Science Writers (NESW) for several years. Our fearless leader, Jim Cornell, told us that we should really join the national organization, and he would sponsor us if we were interested. That must be how I got through the door.

Around that time I got a very interesting project through an announcement at a NESW meeting. A local research institute, Health Effects Institute (HEI) in Cambridge, needed a hand with a multi-author book being published jointly with the National Academy Press in Washington. I signed on, and it soon developed that what they really needed was dynamite to pry the manuscripts loose from a too-enthusiastic copyeditor working in another city. That person's goal was perfection, but HEI just wanted to get the book out. This was in the era when everything was done on hardcopy, so there was only one master version.

A subterfuge was involved that I now forget, but I managed to rescue the chapters. Then I served as production editor, commissioning the art, speccing the design, and coordinating with National Academy Press. The result, Air Pollution, the Automobile, and Public Health (1988), is nowadays posted online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK218150/

So my first job as a NASW member was not exactly science writing, but it was definitely science. — Richard Maurer (NASW member since 1987)

The Canadian Connection

A Special Contribution from the Science Writers and Communicators of Canada (SWCC)

Back in the day, the NASW had a notable membership in Canada. That’s because science writers there didn’t have their own organization, and thus turned to south of the border and became active members of the NASW. But all that changed in in the 1960s as the Canadian members politely and bureaucratically created their own, separate organization.

The details are provided in these excerpts from the new book From Typewriters to Twitter: Celebrating 50 Years of Science Writing in Canada published in 2023 by what is now called the Science Writers and Communicators of Canada (SWCC). — Pippa Wysong (NASW member since 2024), SWCC 50th anniversary book project editor

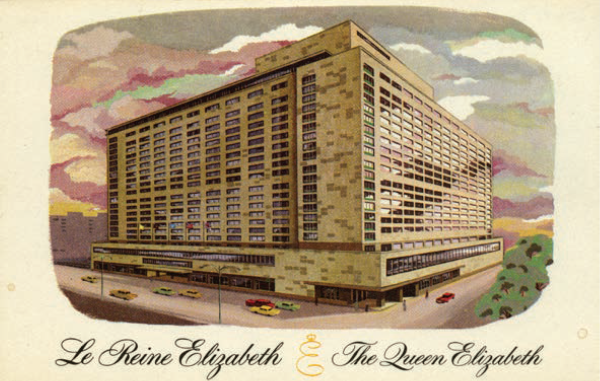

In the beginning: The Canadian Science Writers’ Association (CSWA) did not exist in name until 1971. But the key players in its creation were active members of the National Association of Science Writers (NASW) — an American organization established in 1934. In June 1961, then NASW president Victor Cohn created a committee to address the needs of members of the NASW who lived and worked in Canada. Chaired by Leonard Bertin, and including members such as Fred Poland, David Spurgeon, and Ben Rose, the "NASW—Canadian Committee" was formally established at a meeting at The Queen Elizabeth hotel in Montreal in August 1961. The NASW executive extended formal recognition to the Canadian Committee in December 1961, renaming it the "Canadian Section of the NASW’"

In August 1962, during the second annual meeting, again at The Queen Elizabeth, the Canadian Committee formally adopted the name Canadian Section of the NASW and had powers to elect its own officers. Leonard Bertin was re-elected as chair. Over the next few years, under the guidance of several different leaders and the board of directors, the Canadian Section held its annual meetings in conjunction with the annual conference of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (RCPSC), usually held in January or February. The RCPSC conference was a great source of story ideas for the science writers who attended.

The Queen Elizabeth Hotel as depicted in a postcard, 1962 (Image courtesy of Archives de la Ville de Montréal, file P500Y-2_001-P002)

The Queen Elizabeth Hotel as depicted in a postcard, 1962 (Image courtesy of Archives de la Ville de Montréal, file P500Y-2_001-P002)

Urges for independence: Despite the mere handful of science writers belonging to the Canadian Section, members wanted a Canadian association that was independent of the NASW. At the Section’s tenth annual meeting held in Montreal on Jan. 22, 1970, Section members adopted a resolution to pursue the formation of a Canadian association of science journalists. At a subsequent meeting on May 28, 1970 held in the former Maclean-Hunter Publishing Co. boardroom in Toronto, a motion was passed to prepare a draft constitution by August 1970. (Maclean-Hunter was a leading Canadian publishing company founded in 1887 that was acquired by Rogers Communications Inc. in 1994). On the evening of Oct. 15, 1970, the draft constitution was revised and adopted, and the Canadian Science Writers’ Association (CSWA) was officially born.

The founding meeting, 1971: Tucked away in the boardroom of the Science Council of Canada in Ottawa, the founding meeting for the CSWA was chaired by Earl Damude, editor of The Medical Post. Dr. Omond M. Solandt, chair of the Science Council of Canada, offered the use of the boardroom for the meeting. Present at the meeting were Leonard Bertin, University of Toronto science editor; David Spurgeon, science reporter for The Globe and Mail and editor of Science Forum; Fred Poland, the Montreal Star; Peter Calamai, Southam News Service, Ottawa; Jeff Carruthers, The Ottawa Journal; David Smithers, the Ottawa Citizen; Heather Carswell, The Medical Post (Montreal); Ian J.S. Moore, MD of Canada (Montreal); Ken Kelly, Canadian Press science editor (Ottawa); and Mack Laing, University of Waterloo journalism professor.

Excerpts from the 1962 annual meeting minutes of the National Association of Science Writers (NASW—Canadian Section) held August 22:

"We now have 10 active members. They are Dave Valker, David Spurgeon, Ben Rose, Roland Prevost, Fred Poland, Ernie Myers, Herb Lampert, Rae Corelli, Brian Cahill, Leonard Bertin. In addition, we have four associate members: Doug Veston, Mel Thistle, Ron Kenyon, Duncan Cameron. At least three others are interested in membership: Joan Hollobon, Marc Enri Cote, Jack Livingstone.

“Our Canadian group was formally established at a meeting in this hotel (The Queen Elizabeth, Montreal) last year at this time, originally as the ‘National Association of Science Writers, Canadian Committee’. I would like to remind you of a slight change in the status of our group, vis-a-vis the parent body, since that meeting, as a result of actions taken by the executive of NASW.

“At the December 1961 meeting, the executive formally recognized the existence of the Canadian Section of NASW, and suggested that this name replace that of ‘Canadian Committee’ which had previously been adopted by Canadian members at their Montreal meeting. The document stated:

“To clarify the present situation, then, there are now two Canadian organizations within NASW: (l) The "Canadian Section", formed by Canadian members and comprising all of them, for the purpose of dealing with exclusively Canadian business, and (2) The "Canadian Affairs Committee” of the NASW executive, responsible to the president of NASW, and dealing with Canadian affairs affecting the parent body.”

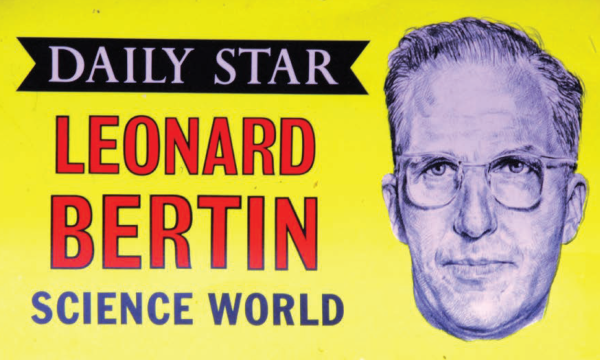

Leonard Bertin, science writer and war prisoner: Leonard Bertin was the first president of the CSWA’s precursor association, the Canada Section of the National Association of Science Writers. He was born in London, England, his father a church vicar who worked with the poor in London’s East End throughout the Great Depression. He studied natural sciences at the University of Cambridge in England before World War II. After the war, he completed his degree in modern and mediaeval languages. During World War II, Leonard served on horseback on the Northwest Frontier of India in a battery of mule-pack ‘screw guns’. Promoted to major, he led an anti-tank regiment in Iraq, Syria, Palestine and the Western Desert. He was captured at the Battle of Tobruk in Libya in 1942, but escaped from a train en route to Nazi Germany, was recaptured three and a half months later and sent to an officers’ POW camp for the duration of the war.

According to his son, Oliver Bertin, his dad learned reporting from other prisoners. They held lectures in the POW camp to help each other rebuild their careers when the war finally ended. He teamed up with some former newspapermen who used clandestine radios to research and publish an internal camp newspaper that was so good their Italian captors dropped by to catch up on the news. Post war, he became Rome correspondent and later the first science editor of the Daily Telegraph. “He had a very interesting time as a foreign correspondent, covering atomic bomb blasts at Woomera and Christmas Island,” Oliver said. His father watched the Bikini Atoll atomic blast tests from a nearby navy ship. In 1957, Leonard emigrated to Canada as science editor of the Financial Post, followed by the Toronto Star and then science editor and News Bureau head at the University of Toronto. A decade later, he moved to Kingston, Ont., as editorial page editor of the Kingston Whig-Standard.

He authored six popular books about science including Atom Harvest (1955), a book that uncovered secret atomic research in the U.K.; The Boys' Book of Modern Scientific Wonders and Inventions (1957); Nuclear Winter (1986) and others. His book Target 2067: Canada’s Second Century (1968), mused about what Canada might be like in the year 2067. He portrayed a world with 15 billion people (a hundred million in Ontario!), moving sidewalks, extensive fish farms, jobs on Mars, and apartment buildings over 200 stories high. He was known for his belief in the immense potential good science could offer, but in later years recognized the challenges.

Poster promoting Leonard Bertin appearing on the side of newspaper boxes. Bertin, the Toronto Star’s science writer, was often stopped on the street by readers who shook his hand and complimented his journalism, recounted his son Oliver to the SWCC. “This was most embarrassing for his teenage kids”. (Photo courtesy of SWCC/Oliver Bertin)

Poster promoting Leonard Bertin appearing on the side of newspaper boxes. Bertin, the Toronto Star’s science writer, was often stopped on the street by readers who shook his hand and complimented his journalism, recounted his son Oliver to the SWCC. “This was most embarrassing for his teenage kids”. (Photo courtesy of SWCC/Oliver Bertin)

Contribute your #NASW90th stories and photos at: https://www.nasw.org/article/nasw-science-writers-90th-anniversary-story...

Founded in 1934 with a mission to fight for the free flow of science news, NASW is an organization of ~3,000 professional journalists, authors, editors, producers, public information officers, students and people who write and produce material intended to inform the public about science, health, engineering, and technology. To learn more, visit www.nasw.org and follow NASW on LinkedIn and Bluesky.

.png)