**By Vrinda Ravi Kumar. Mentored and edited by Jenny Marder.**bal

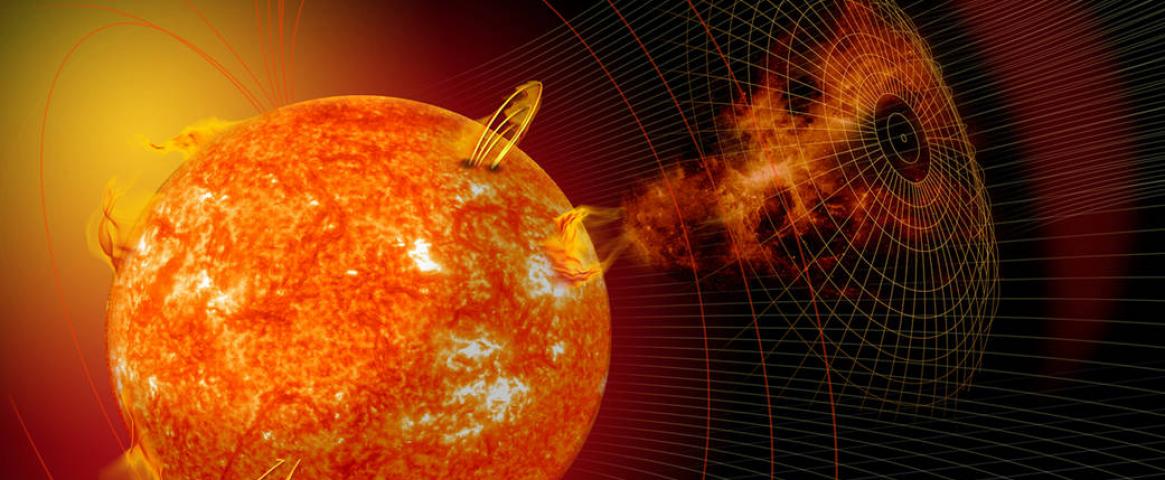

Imagine a colossal blob of plasma spit out by the sun, racing toward the Earth, poised to impact our planet in just three days. These blobs of plasma are known as coronal mass ejections, or CMEs. They result from large eruptions on the surface of the sun, are accompanied by magnetic fields and can grow to hundreds of times the size of our planet.

The public has little awareness of the kind of risks this kind of solar weather poses to our technology, said Delores Knipp, a professor at the Colorado Center for Astrodynamics Research. Knipp was part of a panel of space weather experts who spoke on Feb. 19 at the American Association for the Advancement of Science annual meeting.

When a coronal mass ejection arrives at a magnetized planet, like Earth, Knipp said, “there’s a battle about which plasma and which magnetic fields get to be in charge.”

In fact, if a geomagnetic storm were to hit our planet, it could cause rapid changes in the Earth’s own magnetic field, said Jennifer Gannon, a researcher at Computational Physics, Inc., who also spoke at the space weather session.

A large solar storm can induce currents in long conductors like transmission lines, disrupting our power infrastructure, Gannon said. These currents “can really mess up the systems and cause hazardous conditions for transformers and substations.” Transformers can suffer damage that is difficult to repair or replace, Knipp added. For people on the ground, this could mean power loss for a few hours or significantly longer.

The most intense geomagnetic storm in recorded history occurred in September 1859. Known as the Carrington Event, the solar storm produced “a magnificent display of the auroral lights,” according to the Baltimore American and Commercial Advertiser newspaper. The storm also caused some damage to telegraph lines, Knipp said.

Since that time, humans have developed complicated systems that have both electric and magnetic components.

“We now rely on these systems for a functioning society — think Global Navigation Systems and radio signals of every kind. Thus, we are more vulnerable to solar disturbances than we were in 1859.” Knipp said.

It’s unclear what might happen if a geomagnetic storm of this size were to strike Earth today, Gannon said. One study concluded that a large solar storm “could damage or destroy over 300 high-voltage electric grid transformers and interrupt service to 130 million people with some outages lasting for a period of years,” according to Joseph McClelland, director of the Office of Energy Infrastructure Security, who cited the study at a 2015 Senate hearing on “Protecting the electric grid from the potential threats of solar storms and electromagnetic pulse.”

Instruments on satellites like the Parker Solar Probe, and the SOHO and twin STEREO spacecraft have the capacity to detect and alert us to CMEs traveling in Earth’s direction. Meanwhile, Gannon’s research aims to better understand the potential impacts of a large solar event. A worst-case scenario would be a colossal storm that aligned perfectly with major transmission lines in the U.S. Researchers are working to estimate the vulnerabilities of individual systems if this were to happen, Gannon said. Meanwhile, they're trying to increase awareness among policymakers, utility operators and regulators, and emergency managers, Knipp said.

Sarbani Basu, the session organizer and an astrophysicist at Yale University, concluded the session with this question about large solar storms: “Given that we have so many space weather missions which do give us some warning that a CME has come off and is heading towards Earth ... can we avert a blackout?”

The short answer is we just don’t know. We haven’t had enough large storms to understand the scope of their impact, Gannon said.

But the best response might be a simple one: shutting down power before the storm hits, which would reduce damage to the electrical grid.

“[Power] loads can be reduced, power can be shunted to ground… Really what it comes down to is that you’ve got to turn the power system off.”

Vrinda Ravi Kumar recently completed her PhD in ecology, evolution and behavior at the National Centre of Biological Sciences at Bangalore, India. She is currently working as an R&D consultant. She can be found on Twitter at @vrinzilla and emailed at vrindaravikumar42@gmail.com.

Image: This artist’s depiction shows an active sun that has released a coronal mass ejection. Credit: NASA