This student story was published as part of the 2025 NASW Perlman Virtual Mentoring Program organized by the NASW Education Committee, providing science journalism experience for undergraduate and graduate students.

Story by Pamela Appea

Mentored and edited by Lindsey Leake

As her 40th birthday approached, Maria Gmitro was ready for a “mommy makeover.”

She was done having children, and the way her breasts looked — one was slightly larger than the other — bothered her. In 2014, as a present to herself, Gmitro spent $12,000 on a breast lift and size adjustment.

“I now know it wasn't worth it,” she said.

Breast explants on the rise

Behind liposuction, breast augmentation was the second-most popular cosmetic surgery in the United States in 2024, according to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS). More than 306,100 women had breast implant surgery that year, up from nearly 286,300 in 2014. Yet the reversal procedure has also soared: “explant” surgery among patients who want their implants permanently removed.

Over 41,200 female breast augmentation patients underwent implant removal last year, compared to about 23,700 a decade earlier. Patients may grow tired of a bigger bosom, while others’ implants may be old or deflated. Implants are even recalled at times. Some women, though, seek explant surgery as a treatment for chronic pain, scar tissue buildup or other implant-related symptoms.

For decades, breast implants have been associated with a range of health issues, from cancer to autoimmune diseases. In 1992, while traditional saline breast implants remained on the market, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration halted the use of silicone gel implants in the face of thousands of lawsuits citing adverse events. The agency reapproved their use in 2006.

Still, Gmitro had concerns. Her surgeon waved them away, easing her mind, she said. “‘Remember all those issues from the ’90s with breast implants? They fixed all that,’” Gmitro recalled him telling her. “‘These are the latest and greatest, FDA approved.’”

Breast implants are “mostly” safe — but only “for the right patient,” said Dr. Alan Matarasso, past ASPS president and current president of the Plastic Surgery Foundation (PSF). People with certain autoimmune disorders, for example, may not be suitable candidates.

Gmitro was initially pleased with her implants. Then her hair started falling out.

“It was just some pieces at first,” Gmitro said. Eventually, “chunks of it would come out.”

Within six months, she began to suffer “horrible” insomnia coupled with chronic fatigue. Acne and rashes broke out on her face, chest and breasts. Her skin was slow to heal from cuts, bruises and mosquito bites. Other debilitating symptoms, including migraines and brain fog, led to Gmitro cutting her teaching career short.

Gmitro consulted several medical specialists and was screened for cancer, autoimmune issues and infectious diseases. Having had a bad reaction to an IUD a year earlier, Gmitro wondered whether she was sensitive to medical devices. Yet doctor after doctor told her there was no connection between her worsening symptoms and breast implants.

“I was 40 but I felt like I was 80,” Gmitro said.

She got explant surgery three years later. Over the following months, her health significantly improved.

Safety concerns validated

Gmitro believes she had breast implant illness (BII), a condition of which symptoms may include fatigue, brain fog, joint pain and autoimmune problems. One leading theory suggests that the body rejects implants as foreign objects. Studies have shown that for a majority of patients, BII symptoms improve following explant surgery.

Women’s complaints of the condition were dismissed for decades. While in recent years BII has become more recognized among medical professionals, causal factors remain up for debate.

Diana Zuckerman, president of independent think tank National Center for Health Research, has been studying breast implants since 1990. No human subject research studies were published before implants were put on the market in 1962, according to Zuckerman.

“We know that sometimes some women have a very bad reaction to breast implants and it makes them very sick,” she said. “That's really the bottom line.”

In 2019, a “textured” breast implant manufactured by Allergan that had been tied to breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma, was recalled.

“New doesn’t necessarily mean safer,” Zuckerman said.

The FDA, according to Zuckerman, still hasn’t adequately assessed implant risks. She also believes plastic surgeons aren’t informing patients of them.

While acknowledging that breast implants aren’t risk-free, the ASPS maintains that most women with them “experience no serious complications.” The FDA now recommends MRI screenings five to six years after implantation, then every two to three years, to check for ruptures or other problems.

In conjunction with the FDA, the PSF in 2019 launched the National Breast Implant Registry, in which surgeons can document the implants used in their operations. More than 1,800 registered physicians had entered information from over 143,200 cases as of July 1, 2025.

Gmitro wishes she’d never gotten breast implants and has no plans for new ones. But her experience led her to become a voice for others. Gmitro has since founded the Breast Implant Safety Alliance, a nonprofit that advocates for patient safety surrounding medical devices.

“There’s no standard of care for women with breast implants, especially when they’re placed for augmentation purposes,” she said. “More research needs to be done on breast implant safety.”

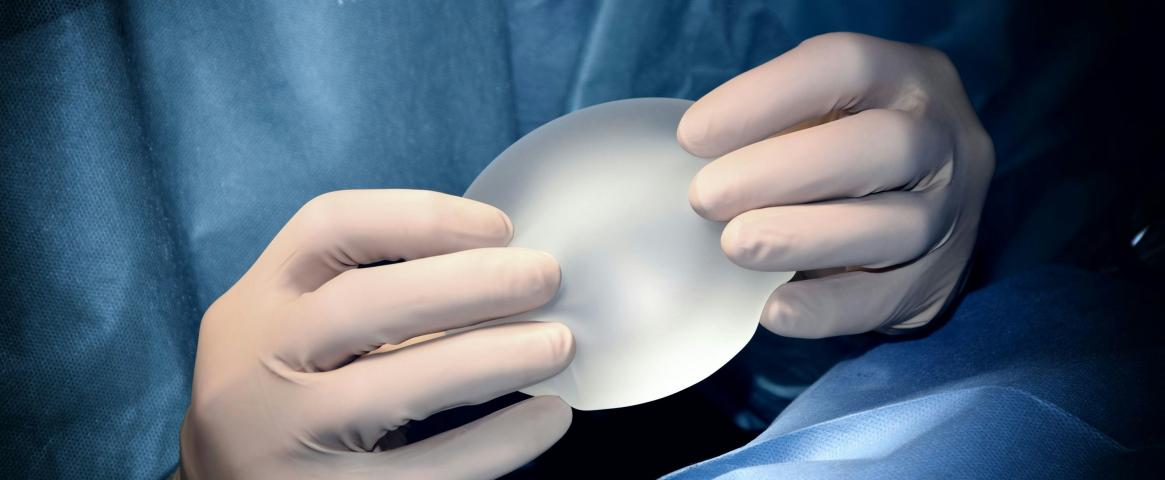

Top image: In this 2021 stock photo, a plastic surgeon holds a new breast implant. Credit: Unsplash. Creator: Philippe Spitalier.

Pamela Appea is a 2024 graduate of CUNY’s Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism. While a student, she interned for WNYC’s “On the Media” podcast and co-produced a project on medical aid in dying that won a second-place AHCJ Award for Excellence in Journalism. Appea is an independent health and science journalist based in New York City whose work has appeared in Wirecutter, Glamour, Parents, Everyday Health, Cancer Today, City & State, Salon, Prism, CNN and The Root. She was a 2022 Age Boom Fellow at Columbia Journalism School and holds a B.A. in English from the University of Chicago. Lindsey Leake is an award-winning, independent health journalist based outside Washington, D.C. Before embarking on a freelance reporting career in early 2025, she spent 15 years as a staffer at news outlets including Fortune, the USA TODAY Network, Sinclair Broadcast Group and WJLA-TV. NASW recognized her article on the shortage of blood donors of color as a finalist in its 2022 Science in Society Journalism Awards. She holds an M.A. in Science Writing from Johns Hopkins University, an M.A. in Journalism and Digital Storytelling from American University and a B.A. from Princeton University.The NASW Perlman Virtual Mentoring program is named for longtime science writer and past NASW President David Perlman. Dave, who died in 2020 at the age of 101 only three years after his retirement from the San Francisco Chronicle, was a mentor to countless members of the science writing community and always made time for kind and supportive words, especially for early career writers.

You can contact the NASW Education Committee at education@nasw.org. Thank you to the many NASW member volunteers who lead our #SciWriStudent programming year after year.

Founded in 1934 with a mission to fight for the free flow of science news, NASW is an organization of ~2,600 professional journalists, authors, editors, producers, public information officers, students and people who write and produce material intended to inform the public about science, health, engineering, and technology. To learn more, visit www.nasw.org.