By Joe Palca

On March 11, I was in New York City because Ira Flatow had asked me to fill in for him as host of “Science Friday.” When I arrived at the NPR New York bureau around 8 in the morning, the first thing I did was check the wires. It was instantly apparent that we would have to change the show. A major earthquake and tsunami had struck northern Japan. I called senior producer Annette Heist and she agreed we should dump one of the segments we had planned, and do something about the natural disaster instead.

Ross Stein, a geophysicist with the U.S. Geological Survey in Menlo Park agreed to come on the program. Stein is a tsunami expert. He was the first guest when the program began that afternoon. Like most people not directly involved in the early hours of a disaster, Stein could speak only in generalities. He knew the tsunami and earthquake were large, but the scale of the destruction was not entirely clear when the show went live on the air. There was no mention of what the tsunami might have done to the nuclear power plants at Fukushima.As I rode back to Washington the next day on the train, I wondered how the NPR science desk was going to cover this natural disaster. Richard Harris was clearly the go-to guy when it came to earthquakes. He had been on “Morning Edition Friday” and did talk about a nuclear power plant that had lost cooling water.

“We’re keeping a close eye on that,” he told host Renee Montagne.

But keeping a close eye on something half way ‘round the world is tricky. NPR no longer has a permanent base in Tokyo, and even when there was a bureau, it was small. We would have had to rely on pictures from (Japanese Broadcasting Corporation) NHK and news reports from the wire services and Japanese newspapers to “keep a close eye” on what was going on in northern Japan even if the bureau had been open.By Saturday night, the scale of the nuclear power plant accident was becoming apparent. Coverage of the natural disaster was still the lead story, but the damage at the Fukushima plants was close behind. Guy Raz, host of “Weekend All Things Considered” told listeners that “all eyes are on that nuclear power plant in Fukushima, about 170 miles northeast of Tokyo. An explosion there earlier today destroyed at least one building. Teams of engineers are scrambling to prevent a meltdown at one of its reactors.”

But for the most part, the information about Fukushima was second or third hand. Press accounts of what was happening differed, as did accounts (such as they were) from the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), owner of the damaged plants. Japanese government sources weren’t much more help.

On Sunday morning, March 13, Richard Harris left Washington for Tokyo, followed a day later by a second NPR science correspondent, Christopher Joyce. That left me with the unenviable task of providing “the latest” for “Morning Edition Monday,” on March 14. Editor Vikki Valentine and online producer Eliza Barclay had been sifting through news reports, websites, and blogs all weekend trying to come up with as much consensus as possible about what was going on, information they fed to me that I regurgitated for a national audience. In hindsight, what I said that morning was fairly close to accurate, but it felt terrifyingly uncertain as I spoke live to America.With Richard and Chris in Tokyo, coverage shifted there. But in truth, access to sources was not all that different from what was available in Washington. The primary advantage was that the televised news conferences were occurring during the day Tokyo time, instead of the middle of the night Washington time. With the help of translators, Chris and Richard monitored events from a room at the ANA Intercontinental Hotel, and filed stories for every show and just about every newscast. On occasion, they were able to garner information from truly knowledgeable sources, but such accurate information was frequently off-the-record, and therefore could only be used to vet the official accounts.

The biggest problem was finding something new to say for “All Things Considered.” It comes on at 4 p.m. Eastern Time, 5 a.m. in Japan. While the circumstances at the Fukushima plant were no doubt changing from moment to moment, the press briefings didn’t start until much later in the day, local Japan time. That didn’t stop “All Things Considered” from wanting “the latest news from Japan,” so a bleary Chris or Richard (and later Jon Hamilton, who relieved them) would have to come up with something they hadn’t said eight hours earlier on “Morning Edition.”

I left for Tokyo on March 31 to relieve Jon. By the time I arrived, the nuclear story had cooled down, if you’ll forgive the pun. If you had never been to Tokyo before, which was the case for me, there was little evidence by then that there had been a major natural disaster in Japan a month earlier, never mind any indication that a nuclear power plant was still not safely shut down. Yes, there were escalators that were shut off to save energy, as well as many lights that once blazed through the night. But otherwise, to the untrained eye, it was pretty much business as usual.

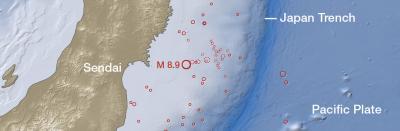

NASA Earth Observatory image showing the epicenter of the March 11 magnitude 9.0 earthquake 130 kilometers (80 miles) east of Sendai, Japan, which sent tsunami waves rushing into the coast of Japan and rippling out across the entire Pacific basin. (sources: earthobservatory.nasa.gov and earthquake.usgs.gov)There were still daily briefings in Tokyo about the Fukushima plant, but they weren’t always televised, so it was a bit harder to keep up with what was going on. Every day the foreign ministry held briefings for foreign media that were either in English or included simultaneous translations, but these briefings were typically a rehash of what had been presented earlier in the day for the Japanese media. The biggest news while I was in Tokyo was a strong aftershock that shook me out of bed at around 11:30 at night. For an hour or so there were concerns about a second tsunami, but that never materialized.

There was no point in traveling to Fukushima to cover the nuclear story. No reporters were getting in to the plant. I requested a ride on one of the Department of Energy planes that were sent to Japan to help monitor airborne radiation, but my request was turned down.

Did NPR give people in the United States an accurate picture of what was happening at the Fukushima plant in Japan? I feel we did. It was a true nuclear disaster, comparable to but not as bad as Chernobyl. It was not the cataclysm some other news organizations made it out to be. But the whole experience leaves me uncomfortable. People who really knew what was going on either weren’t talking or weren’t allowed to talk, and everyone else was talking non-stop without benefit of all the facts. We’ll really know whether we did a good job when the spate of accident reports appear in the coming years. One thing I do know. We did the best we could.

Joe Palca is a science correspondent for National Public Radio.

(NASW members can read the rest of the Summer 2011 ScienceWriters by logging into the members area.)