By Jennifer Cutraro

When I tell people I write about science for kids, I usually hear an enthusiastic "Oh, that must be so much fun!" More on that later. The second thing I hear is "How did you get started?" Breaking into kids' writing is much like breaking into any other kind of writing. Know the market, network with editors and other writers, and practice, practice, practice.

That last bit is especially key. Writing for the under-18 crowd is not as easy as you might think.

Know your audience

The voice you use when writing for kids isn't the same one you'd use for a post on Wired.com or a profile in the New Yorker. If you want to write for kids, read a bunch of magazines or websites that target this audience. Check out sources such as Science News for Students, Scholastic Science World, or National Geographic Kids to get a sense of the language level appropriate for this age group. Pay attention to sentence length, paragraph structure, and word choice. Compare a kids' science story to a story on the same topic written for adults.

You'll quickly see that writing for kids means simple sentences and straightforward explanations of science concepts. The ledes are tighter, more direct, and often grounded in a kid's personal experience. Other tips? Avoid jargon. Use action verbs and sensory descriptions. Don't cover more than one science concept per sentence — or better yet, per paragraph. Use comparisons with which kids will be familiar.For example, Douglas Fox avoided high-level concepts such as the thermodynamics of particles in clouds to explain why ice particles, and not water droplets, are necessary in raindrop formation. "I sidestepped that morass and went with the intuitive metaphor: touch your wet tongue to an ice cube fresh out of the freezer and it will stick to it -- just like stray water molecules stick to an ice crystal in the cloud," he says.

Think, too, about what kids may or may not know. The things that you need to spell out in a kids' story might surprise you. As Helen Fields, who recently wrote her first story for kids, explains, "You can't assume any of the bundle of vague knowledge that adults have collected along the way. I actually had to explain what a router and a cable modem and resin are, and it was seriously difficult."

Don't talk down to kids

Kids are savvier and smarter than a lot of people give them credit for. Don't dumb down your language for them or shy away from difficult ideas. "You might spend more time explaining what you mean and breaking concepts down," says Amanda Mascarelli, "but it doesn't mean that you don't delve just as deeply into the science."

Don't use gratuitous exclamation points, either. "I see so many examples of writers either talking down to kids or writing sentences that are way too convoluted to make sense to a young person," says Emily Sohn. "You can't just put an exclamation point at the end of a sentence and think that your writing is now kid-friendly!" It's a particular pet peeve of mine as well.

And don't assume that science stories need to be zany, wacky or outrageous just to hold kids' attention.

"I don't use many 'guess what?' or 'can you believe this?' — type questions in my kids' writing," says Stephen Ornes. Neither do I, nor do most of the kids' writers whose work I admire and respect.

Just as with writing for adults, strong characters and a compelling narrative will keep your readers with you from start to finish. Keep in mind the characters, setting, and adventure inherent in many science stories. Who are the scientists? Where are they? What drives their curiosity? How are they exploring their questions? How did they arrive at their conclusions?

Find ways to interact with kids

Sarah Webb, who worked at a science museum before becoming a science writer, stresses the importance of actually being around kids if you want to write for them. "If you don't keep them in mind, you'll lose the awe and wonder that makes kids' writing fun," she says. She encourages would-be kids' writers to talk about science with kids, either through teaching, volunteering, or with kids in your own family.

Emily, who led field expeditions for middle-school kids before becoming a science writer, agrees.

"[Experience with kids] gives you that window into the way their developing brains work and what kinds of questions they ask," she says.

Like Emily and Sarah, I was an informal science educator before breaking into writing. That direct experience with kids helped me to think about science through the eyes of a 12-year-old reader, knowing the kinds of questions they tend to ask, the experiences they tend to have, and even the pop cultural references that will work in a story.

Don't assume it's easy

My informal poll of fellow SciLancers who write for kids uncovered a few misconceptions: that writing for kids is fun and easy — or worse, that it's just something people do when they can't sell a story to a publication for adults.

"Because it's simpler language, people sometimes think that anyone can do it," Sarah says. "It's hard work to do it well. You also have to be more proactive in interviews, making sure sources give you simple answers, particularly if you want to quote them."

Plus, Stephen points out, "Many stories are harder to tell to kids than to grown-ups. You have to have such mastery of the study that you can explain it to a 10-year-old."

He's right — just try explaining terahertz radiation in terms a fifth-grader will understand.

Most writers agree that writing for kids makes their writing better overall. "[But] I find that it really pushes me to know exactly what I'm trying to say, and if I don't, then to figure it out," Amanda says. "Writing for kids stretches me as a writer, and some of my favorite clips are the ones I've written for kids."

Doug concurs: "I think that writing stories for kids several times per year actually helps me to be a good writer for regular adult audiences."

And yes — we all do enjoy writing for kids. I'll even use the f-word and admit writing for kids can be a heck of a lot of fun. As Emily points out, "You can also play up things that are totally gross, which is one of the perks."

Let's hope we are all doing our jobs well — it's today's kids, after all, who will be reading our science stories well into the future.

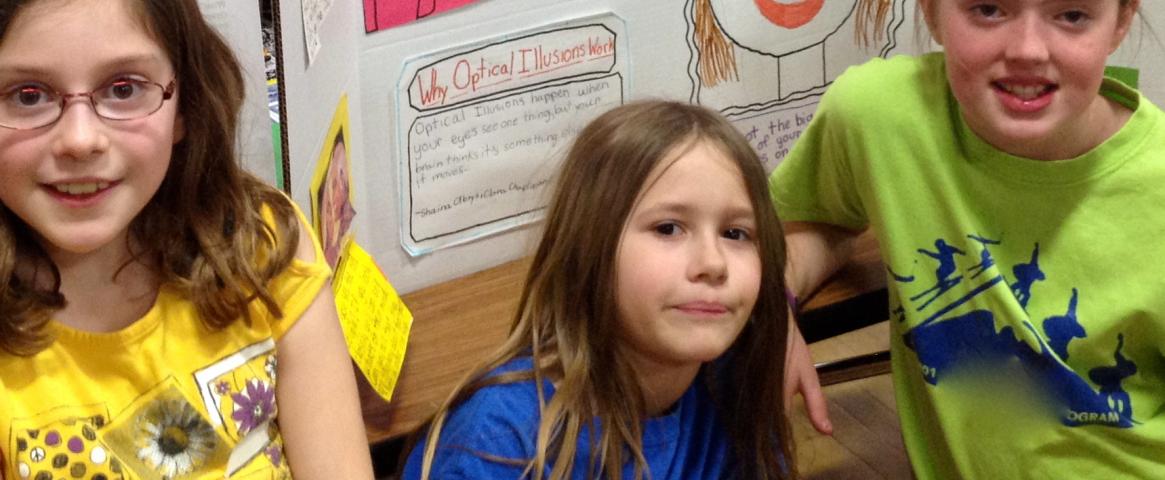

Jennifer Cutraro is the founder and director of Science Storytellers, a program that gets kids to interview scientists just as professional journalists do — and to then share their stories. She also has written for the Boston Globe, PBS KIDS, Science News for Students, and the New York Times Learning Network.

Image credits: Jennifer Cutraro and John Chaplin