Story by Jude Coleman

Photography by Claire Cleveland

When writing narrative pieces, journalists must rely on more than their witty word craft to bring a story alive – but finding color for stories is an acquired skill. At the ScienceWriters2022 national meeting in Memphis, a panel of storytellers laid out their top tips for getting the most out of interviews.

Organized by freelance science writer Katharine Gammon, “What Do You Mean By That? Interviewing For Narrative Science Stories” (#SciWriNarratives) featured journalists from a range of media mediums: Esther Honig, a producer at StoryCorps; Craig Welch, a climate and environment writer at National Geographic; and Simon Adler, a senior producer at Radiolab. All three agreed the key to getting delicious quotes and tasty anecdotes for a piece is to get your source to tell a story. If you can’t get enough details the first time, circle back later in the interview.

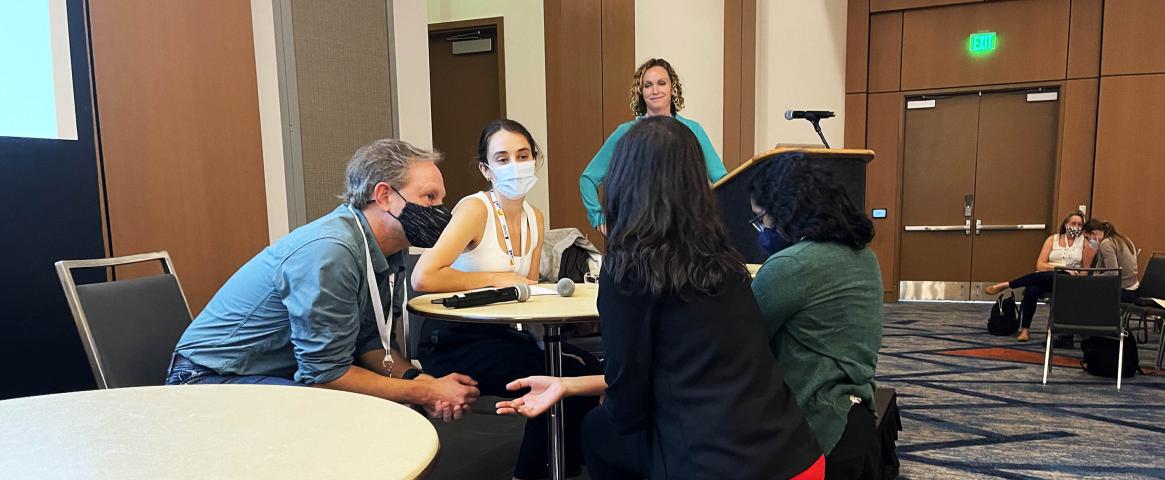

Participants practiced fishing for anecdotal answers in a 10-minute breakout as part of this session. Pairs of science writers teamed up to interview each other about a recent moment of surprise, or the closest they came to believing in the supernatural. All the while putting the workshop panelists’ tips into practice.

“Keep going at it. Don’t be ashamed of asking the same question over and over again,” Welch said, citing one interview where he repeated a question over ten times. If all else fails, he recommends giving sources an example of the type of detailed answer you’re looking for.

Attendees interview one another during the SciWriNarratives workshop at ScienceWriters2022. (Claire Cleveland for NASW)

Attendees interview one another during the SciWriNarratives workshop at ScienceWriters2022. (Claire Cleveland for NASW)

Anecdotes recreate images and sensations that your source — the story's main character — saw and felt in the moment, painting a scene for readers. The panelists said that thinking about the scenes within a story can help guide interviews. Adler suggests imagining interview questions as video shots: wide angle, first-person, and reactionary. Wide-angle questions set the scene and give an overview of the story; first-person questions add detail; reactionary shots draw out the person’s emotions in the moment.

“You're trying to get visual detail and you're trying to get sensory detail,” Adler said.

Welch used his 2018 story “The Big Meltdown” as an example of getting good narrative content. The piece highlights how climate change is sweeping through Antarctica and features Dione Poncet, a born-and-raised Antarctician. But in the month Welch spent with Poncet sailing around the Antarctica Peninsula on an 87-foot boat, he struggled to get more than sparse, basic answers to interview questions. Welch had done his research, though — he came into the assignment prepared with background knowledge about Poncet’s life and knew he wasn’t much of a talker. Having that background knowledge paid off: when typical interview questions yielded little, Welch whipped out a detail from Poncet’s past.

Attendees interview one another during the SciWriNarratives workshop at ScienceWriters2022. (Claire Cleveland for NASW)

Attendees interview one another during the SciWriNarratives workshop at ScienceWriters2022. (Claire Cleveland for NASW)

“Finally, I said, ‘Well, your mom said that she would make you go out and count penguins. Could you tell me about that,” he said. Though a small detail, it gave Welch the fodder he needed to flesh out a few paragraphs on Poncet’s Antarctic upbringing. “It's a perfect example of the kind of color you can get by being able to throw a little bit of detail back at somebody.”

Doing your homework before an interview will give you specifics to discuss if details aren’t coming up naturally. At the same time, “allow yourself to ask stupid questions,” Honig said. Sometimes in an effort to assure a source you’re informed, you may end up hearing only half the story.

On top of getting juicy bits for a story, Honig offered other good practices for successful interviews. As uncomfortable as it may be to sit in silence, resist the urge to fill gaps with extra commentary. When we chime in too early, it robs the interviewee of their chance to think things over and respond more, she said. Keep questions short and straightforward. And at the end of your interview, take a moment to decompress with sources and express your gratitude.

“Acknowledge how grateful you are that they chose to spend some of their time with you,” Honig said.

Jude Coleman (@JudeLB_Coleman) is a freelance science writer covering climate, ecology, and environmental justice.

Claire Cleveland (@ClevelandClaire) is a freelance journalist covering reproductive health & justice and LGBTQ+ health and aging.

This ScienceWriters2022 conference coverage article was produced as part of the NASW Conference Support Grant awarded to Coleman and Cleveland to attend the ScienceWriters2022 national conference. Find more 2022 conference coverage at www.nasw.org

A co-production of the National Association of Science Writers (NASW), the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing (CASW), and St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, the ScienceWriters2022 national conference featured an online portion Oct. 12-19, followed by an in-person portion held in Memphis, Tenn. Oct. 21-25. Learn more at www.sciencewriters2022.org and follow the conversation on Twitter at #SciWri22

Credits: Reporting by Jude Coleman; edited by Ben Young Landis. Photography by Claire Cleveland; edited by Ben Young Landis