By Meg Dalton

David Perlman discovered his interest in science by accident. An actual accident. It was 1957, and he was in the hospital recovering from a ski injury. His friend, a pediatrician at the same hospital, stopped by his room one day and dropped off a book, The Nature of the Universe.

"I've told this story a million times," jokes Perlman, 98. "When an old guy tells a story of his past, every time he tells, it will be a bit different."

In the book, author and British astronomer Fred Hoyle describes his theory on the origin of the universe. Perlman remembers telling his friend: "Come on, I don't care about that stuff. I'm not interested in astronomy or anything else like that."

But Perlman was confined to his bed with not much else to do. So he read Hoyle's book, and the wheels in his brain started turning. "Hmmm, so this is what astronomers do," he remembers thinking at the time. He wanted to know more, and as soon as he recovered, he hiked up to the summit of Mount Hamilton, just east of San Jose. There sat Lick Observatory, an astronomical observatory operated by the University of California. Perlman met with Dr. George Herbig, who later developed a reputation for pioneering work on the birth of stars. Their conversation was short, and the questions were simple."Oh, sir, what do you do for a living?"

"I study stars that are being born in the Orion nebula."

It was an epiphany for Perlman, this idea of stars being born. "I thought it was one of the most romantic ideas I'd ever heard." It cemented his interest in astronomy, though not enough for him to study it. Writing about it was the next best thing. At the time, the San Francisco Chronicle, where he's worked on and off for 77 years, didn't have a science reporter. He talked to more scientists, not just astronomers, but physicists and chemists. "One thing led to another, and then that was all I wrote about," Perlman says.

Fast forward 60-plus years. Perlman is retiring from journalism. He's been a science writer through it all: The discovery of Lucy, Dolly the Sheep, the identification of exoplanets, the AIDS epidemic. He has a clip of his first story about AIDS on his office wall. It's maybe 12 or 15 inches long and was published in June 1981, around the start of the global scourge.

"'A pneumonia that strikes gay males,' that's the headline," he reads. "At the time, we didn't think it was important enough to stick a byline on it."

Perlman was born Dec. 30, 1918. His mother's boyfriend, who was a reporter at the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, took him to a screening of The Front Page when he was 12. The comedy features fast-talking, tabloid newspaper reporters on the police beat. "I wanted to be like those guys in the movie," he says. Even today, Perlman keeps a quote from the film in his study: "Seedy, catatonic Paul Reveres, full of strange oaths and a touch of childhood."His career didn't turn out exactly like that of the characters in the film. He first dabbled in journalism at his junior high school's newspaper, then the high school's, and eventually the Columbia Daily Spectator while an undergrad at Columbia College. At 18, Perlman landed his first professional gig as a journalist. It was the summer of 1938, and he was working at a newspaper in Schenectady. The New York native was recruited by a former Spectator managing editor, Mike Gravino, to cover local news for his Sunday paper.

"The one thing I remember about that experience is I wrote a story about an ex-con who complained about brutal treatment in Schenectady county jail," Perlman says. "And we wrote a story based on my interview with him. The sheriff sued the paper for libel, but nothing ever came of the lawsuit."

He's published thousands of stories since then. If you search the San Francisco Chronicle's archives, there are more than 3,000 stories with his byline. When I ask him if he's ever missed a deadline, he laughs, "Of course, who hasn't?" He remembers one time, back when newspapers used linotype machines, when his editor told him to dictate his story to the machine operator. "I was running into the newsroom, and I went back into the press room to make the deadline," he says.

He began at the Chronicle as a copy boy after graduating from Columbia College in 1939 and then from Columbia's School of Journalism in 1940. He briefly worked at a newspaper in Bismarck, N.D., right after graduation, but didn't care much for the city. Paul C. Smith was the editor in chief of the Chronicle when Perlman joined the team in July of 1940. He describes Smith as a "wonderboy of journalism," who, at the age of 26, assumed editorship of the paper. He had ambitions of making it the "New York Times of the West."

After the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Perlman, knowing he'd be drafted, enlisted in the army. "I didn't do anything in the war," he says. "I was part of Army Air Corps briefly and ended up in the infantry, but never fired a shot, or got shot at."

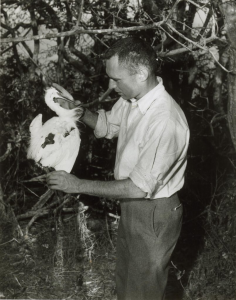

World War II ended in September 1945. Perlman stayed in Europe to work as a reporter for another six years. On a whim, he had called the editor of the Paris Herald, (the European edition of the New York Herald Tribune), for a job. In 1951, Perlman and his wife returned to San Francisco to raise their children. He resumed reporting at the Chronicle, where he's been ever since.At the Chronicle, Perlman has had complete freedom to cover an unusually wide range of topics, from medicine to astronomy to climate change. He's also traveled everywhere for the paper: Germany, Ethiopia, Antarctica, and, his favorite, the Galapagos Islands. Following in the footsteps of Charles Darwin, he joined a team of 40 or so scientists studying evolution on the island in 1964, returning with other teams in subsequent years. "Stories that deal with species and evolution are my favorite to report," he says.

His interests expand beyond "the origin of species." He wasn't the first person to do it, but he remembers trying to explain "greenhouse gases" to his readers. It was during a time before the phrase "climate change" entered the zeitgeist. "It was hot stuff," he deadpans. For Perlman, like many journalists, getting people to care about climate change is a challenge. It's an abstract issue, far removed from the everyday lives of most Americans. It hasn't gotten any easier in the increasingly divisive political environment. "Our job is to write about what we know are the ominous elements of a changing climate and hope that the readers will believe what we write," he says. "All I can do is to write as convincingly and persuasively as possible."

In general, Perlman believes interest in science journalism has diminished. "The media, including my own newspaper, do far less reporting about science today than in the past," he says. "Science journalism today is not what it was when A.M. Rosenthal conceived of it years ago." The former executive editor at the New York Times, Rosenthal led the news giant through 17 years of record growth, including the launch of the Science Times section on Tuesdays.

Though places like the Times have a robust climate team, there's been a decline of general science coverage, with the exception of medical, health, and wellness stories. Between 1989 and 2013, the number of science sections in major newspapers dropped from 95 to 19. "Most newspapers I'm aware of don't cover ongoing developments in physics and astronomy and all the subjects I've written about over the years," Perlman says.

Perlman's been witness to changes not only in science journalism, but the industry as a whole. When he started, typewriters and telexes were the norm in the newsroom. Now it's Twitter. Reluctantly, he started a Twitter account (@daveperlman) after some persuading by his Chronicle colleagues. But it got hacked. Perlman hasn't bothered with it since. "I don't tweet," he says. "I don't care."

What he does care about is good journalism. It's one of the reasons he decided to retire. "I'm getting too old to do a decent day's work," he jokes. "It's just time. My legs are creaky." If he were the average American, Perlman would have retired in 1982. But he was having too much fun. "Be a reporter," he says. "It's the best job in the world."

His last story, co-reported with his colleague and friend Steve Rubenstein, was about the August solar eclipse.

Now that he's finally retiring, Perlman doesn't plan to slow down. He's toying with the idea of writing a memoir on his life as a reporter. "I'm going to steal everything you write for this piece," he jokes. Audrey Cooper, the Chronicle's editor in chief, also suggested he become "Science Editor Emeritus." He can keep his office and also still access the news organization's computer system. He even plans to file the occasional freelance piece.

"I'm going to be around here," Perlman says. "The only thing that's different is I won't get a salary."

Adapted from "After a lifetime covering science, 98-year-old retires from 'best job in the world,'" Columbia Journalism Review, Aug. 2, 2017.

Meg Dalton is a CJR Delacorte Fellow.

(NASW members can read the rest of the Fall 2017 ScienceWriters by logging into the members area.) Free sample issue. How to join NASW.