By Kayla Wiles

BOSTON — The way you first learn to construct and articulate sentences early in life might not be the speech pattern you hang on to the longest as you age and lose mental acuity. This thought goes against common beliefs about language loss among people living with Alzheimer’s disease, but is borne out by recent studies among youth, older adults and multilingual individuals.

“There are significant changes … changes that I don’t think have been noticed before,” said Barbara Lust, a developmental psychologist and linguist at Cornell University, during a Feb. 19 panel at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) annual meeting. “We don’t think that, in fact, the regression hypothesis holds and explains them.”

The period between the onset and full development of dementia, called the prodromal period, can last as long as 15 to 20 years. That is essentially considered the intermediate stage between “healthy aging” and dementia.

To determine when healthy aging gives way to cognitive impairment, Lust and Janet Cohen Sherman, a clinical neuropsychologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, compared children’s language use with that of “healthy aging” individuals, “healthy young” individuals and individuals with mild cognitive impairment. Among other things, they tried to identify when it became more difficult for people to mentally process and use clauses that start with words such as “what” and “which” — so-called relative sentence clauses — when they speak. These clauses are among the easiest and earliest concepts that children understand and learn to apply in a sentence. A kiddie example of such a sentence is “Big Bird eats what hits Ernie.” An adult example of this sentence type might be, “The philosophy teacher pondered what the researcher said.”

Although the ability to recall words and connect concepts with sounds deteriorates over time for both healthy aging adults and those who are cognitively impaired, the reason and results are different for each. Healthy aging adults struggle due to the “tip of the tongue” phenomenon, in which they remember the concept of a word or how it is used, but have trouble recalling the word itself. Cognitively impaired individuals, on the other hand, may understand the word itself, but forget or confuse the concept behind its use.

Lust and Sherman found that healthy aging individuals were able to use “what” correctly in a relative sentence clause because they had retained their ability to process that concept. In contrast, those who were cognitively impaired lost very early the ability to apply that concept, which was among the first learned in childhood. To compensate, those persons would often substitute “that” for “what.” “What was easiest for the child was a huge challenge for the impaired,” Lust said. It would be useful, then, to incorporate language cues into cognitive tests used to screen for Alzheimer’s disease, the researchers said. Current tests include items such as assessment of memory, decision making and the ability to indicate the names of things.

“Doctors typically administer cognitive screens, but they’re light on language,” Sherman said. “If you’re going to do this early, you’re going to have to get much more complicated than asking someone to name an object.” Language tests used in the study, including assessment of the ability to form sentences and put words into categories, could complement existing screening processes, the researchers said.

Other insights for new language-based tools for both screening and therapy come from studies of language loss among multilingual individuals. Findings from some of these studies also conflict with the regression hypothesis about the order in which language skills are lost.

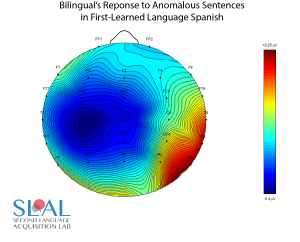

In a study of native Spanish speakers who learned English as a second language, for example, Gita Martohardjono, a linguist at City University of New York Graduate Center, tested what happened to the participants’ command of Spanish when English became dominant in their daily lives.

Using EEG to measure brain activity during listening tasks, the researchers found that those who used English more dominantly responded less dramatically to grammatical errors in Spanish than those who used English less frequently. This led to the conclusion that the level of Spanish that speakers retained over time depended more on their current use of English than on the fact that they had learned Spanish first. This suggests that clinical therapy for multilingual individuals with Alzheimer’s disease should address retention of all languages a person speaks or spoke.

“When you do therapy for any language-related condition, it’s easy to think, ‘Well, let’s just do therapy on the native language,’” Martohardjono said. “But we should try to find out how many languages the person speaks, even if there are languages that they are perhaps not using anymore.”

Kayla Wiles is a senior health journalism major at Furman University in Greenville, SC. She is a health columnist for The Paladin and an editorial assistant for Iron Disorders Institute. She has interned at the Greenville Journal and Action on Smoking and Health (ASH) Scotland. Reach her at wiles.m.kayla@gmail.com or tweet @PeriodistaKayla.