By Jill U. Adams

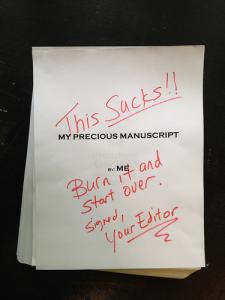

You get your assignment. You report and write your story. You get back the edits and your piece is covered in red.

Me too.

Even though I'm an experienced health journalist, who has been a regular contributor to the Los Angeles Times and the Washington Post, I still see plenty of red.It's no small task writing an 800-word health column — one that's based on research science, delivers appropriate context, acknowledges open questions, and avoids whiplash or ambiguity. So when I see red, I try not to beat up on myself too much.

Information overflow

Some assignments lead me to an overflowing trough of research. I can get so bogged down in journal article details that I may gloss over context. After reading and thinking and talking to study authors, I sometimes fail to realize how much I've learned in the process and I forget to lead the reader along with me. (It reminds me of my mother playing Trivial Pursuit. When she knows an answer, she presumes everybody knows it!)

Another pitfall I repeatedly tumble into is reporting what I find and ignoring the pertinent questions for which I didn't find answers. Or — and this is embarrassing to admit — I fall in love with a finding or idea and include it in the story even though it doesn't serve my purpose. In the process I end up racing through the basics.

This is why I need an editor — to remind me to add context, to ask the unanswered questions, and to call me out when I'm flirting with tangents. And if I have a good working relationship with an editor, I never mind the red ink. (Okay, it's not really ink. Red pixels?)

Remember the basics

In a 2011 piece I wrote for the LA Times on the so-called morning-after pill, I needed to get readers to get up to speed on the policy developments before I dove into the science, the "Why does this matter now?" part of the story.

Guess what? I glossed over it, prompting this note from my editor, Rosie Mestel (now at Knowable Magazine):

The drug was approved for over-the-counter sale in YEAR, but concerns from WHO about WHAT led the Food and Drug Administration to WHAT in the case of girls 16 and younger. The concern was WHAT. [We need a bit of orienting background I think.]

Oof, right. (I should have thought of that!)

In that same story, I got so bogged down in stats (such as the proportion of 11-year-old girls who are menstruating and the proportion who are having sex) and studies (such as changes in contraceptive use or sexual activity when Plan B pills are freely available), that I failed to give voice to the anti-abortion proponents, who characterize morning-after pills as abortion-causing. Rosie noted:

[We need to talk to someone about their objections to plan b being over the counter for 16s and under.]

Yes, of course. (Why didn't I consider that?)

Cut the extras

I love parsing policy debates, which means sometimes I get in a little deep. For instance, in this 2013 Washington Post story about direct-to-consumer advertising of drugs, I wrote:

The main argument for DTC ads is that they are protected as free speech. That fact alone has most opponents of the practice looking at ways to counter the ads' powerful messages rather than outlaw them.

My editor, Pooh Shapiro, deleted it. I have so few words to work with, I don't have room to wander from my primary focus. She reminded me thusly:

The question is how these ads affect our health.

Um, good point. (But it's fascinating! And that's why the U.S. is different! And … oh stop.)

The beauty of a good working relationship with an editor is not learning to love red. But it is accepting that when you dive into a topic and do a ton of research over a short period of time, you can only do so much.

You try to put things into context, but you also include the interesting nugget that you learned from your reporting. Then you submit your draft and let your editor — as a seasoned second set of eyes well-versed in the publication's purpose and readership — do her job.

She'll rein in your obsessions, she'll nudge you to find another voice, and she'll make your story better.

(Note: Plan B has since been approved for use by all ages without restrictions.)

Jill U. Adams is a science journalist who reports on health, biomedical research, psychology, education, and the environment. She is a health columnist at the Washington Post and an editor for several online publications.

Image credit: LMRitchie via Flickr/Creative Commons

Image credit: Ak~i via Flickr/Creative Commons