On science blogs: Court of opinion

GENETIC IGNORANCE AT THE SUPREME COURT IS PATENTLY OBVIOUS. The Supreme Court decision yesterday (June 13) declaring that Myriad Genetics' patent on BRCA genes isn't valid seems — at least in large part — like a victory for logic and rational thought. It's being interpreted widely to mean that any gene that exists in nature is not patentable, even though some lab work is involved in isolating it.

The SCOTUS Blog is usually the place to go for clear, succinct analysis. Lyle Denniston says:

biotech researchers have to create something to get monopoly protection to study and apply the phenomenon. Because Myriad Genetics, Inc., “did not create anything,” the Court struck down its patent on isolating human genes from the bloodstream, unchanged from their natural form. Because Myriad did create a synthetic form of the genes, however, that could be eligible for a patent, the Court concluded.

So, according to this analysis, Myriad's patents on the genes BRCA1 and BRCA2, which have several mutations that greatly increase the risk of breast and ovarian cancer, are not valid. And by implication neither are other genes. But a patent on cDNA created from those genes might be.

The inside-baseball interpretation at Patent Docs, the biotech and pharma patent law news blog, sounds somewhat different to me, with the proviso that I'm ignorant of patent law and may be missing some subtleties here. I'm quoting at length to give you the snotty flavor. Kevin Noonan opines:

While the biotechnology industry avoided a categorical ban on patenting DNA … or, worse, on "products of nature" no matter how altered, the Court's carefully focused opinion contains enough worrisome dicta to permit plaintiffs to declare victory even though the Court expressly disclaimed any decision on genetic diagnostic methods (which, after all, was the purported basis for the litigation in the first place).

This is quite a long post, and it agrees with the non-patent-expert commentary that the Supremes need to spend their summer vacation in a remedial biology class.

Despite the glaring scientific and technological weaknesses of the Court's opinion, it does not (fortunately) invalidate thousands of existing patents or sufficiently upset the "settled expectations" of the biotechnology community. But the opinion is another data point on a trend of the Court imposing its opinion of what is patent eligible on grounds that come perilously close to "we know it when we see it," a standard that works even less well for patenting than it did a generation ago for pornography.

From an appended comment to this post:

Let's definitely not get lost in the media and ACLU hyperbole about this case being about "patenting human genes" which it was not … the Myriad opinion is essentially applicable only to that 2% of the human genome that follows the pre-ENCODE approach to genetics. That means that the Myriad opinion is really inapplicable (i.e., not on point) as to 98% of the human genome that doesn’t follow the pre-ENCODE approach to genetics. So keep your chin up, the “game” isn’t over yet by a long shot.

I'm not sure what a patent lawyer means by "the pre-ENCODE approach to genetics," as if nobody knew about that 98% of the human genome until the ENCODE project dove into it. Which is just silly. But to me this sounds like hand-rubbing glee at the prospect of patenting the entirety of the non-coding genome, including regulatory sequences and all the other epigenetic bells and whistles. You know, the part that turns on and off the coding 2% of DNA. The part that makes it actually do stuff.

Scary.

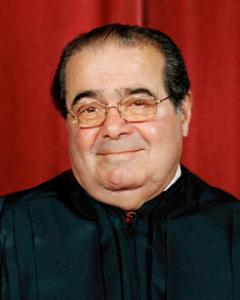

JUSTICE ANTONIN SCALIA: GENETIC IGNORAMUS OR CUNNING WORDSMITH? The decision was unanimous, and how often does that happen? Even in a case like this, where an acknowledgement that human genes are products of nature, not inventions, are (as lawyer and science writer Kathiann M. Kowalski titled her post at Summa Cum Latte) "Patently Obvious." Another oddity was that Justice Clarence Thomas, who is well known for speaking not a word at Supreme Court hearings, wrote the decision. Denniston observed

Justice Clarence Thomas’s opinion for the Court ran only to eighteen pages, but those were densely packed with virtually impenetrable references (for the lay person) to such things as nucleotides, covalent bonds, introns, exons and pseudogenes. Many readers no doubt will share the view of Justice Antonin Scalia, in a short, separate opinion refusing to join in a section “going into the fine details of molecular biology,” of which he said he had neither knowledge or belief.

Justice Scalia is, of course, notorious for his contrarian views. He said he joined the judgment and all of the court's opinions except for the technical stuff

going into fine details of molecular biology. I am unable to affirm those details on my own knowledge or even my own belief. It suffices for me to affirm, having studied the opinions below and the expert briefs presented here, that the portion of DNA isolated from its natural state sought to be patented is identical to that portion of the DNA in its natural state; and that complementary DNA (cDNA) is a synthetic creation not normally present in nature.

This proud (or maybe sneering?) declaration of deliberate ignorance about details crucial to his decision is on its face startling, even shocking. But it is also puzzling, especially on close reading. Scalia was perfectly willing to take the word of experts that the patented DNA was natural, not invented, and therefore unpatentable. But about the underlying details of molecular biology: "I am unable to affirm those details on my own knowledge or even my own belief."

I wonder if he meant that he wasn't sure that the law clerks who presumably wrote that background section got it right?

Kevin Noonan, the patent lawyer cited above, reads the Scalia comments rather as I did — although I hasten to add that the compliments are exclusively Noonan's.

Justice Scalia's concurrence is remarkable for its intellectual humility and honesty; the Justice refuses to join the portions of the opinion "going into fine details of molecular biology," the Justice stating that he is "unable to affirm those details on my own knowledge or even my own belief." Would that the remainder of the Court had come to this realization.

There have, of course, been some predictably scathing posts about know-nothing Scalia. See, for example, Max Read's fulmination at Gawker. I am shocked to find myself inclined to cut Scalia any slack, but I'm not sure contempt is entirely deserved in this instance. Maybe Scalia is more scientifically savvy than it might appear?

Or at least cautious. Because — as it happens — whoever wrote those sections didn't get the science right, quite. Ricki Lewis pointed out some genetic errors at DNA Science, errors that are not huge, but are odd and even careless when definitional accuracy of the right kind is only a Google away. The decision defined cDNA correctly as "exons-only strands of nucleotides" but at first mention called it "composite DNA" instead of complementary DNA. (The terminology was correct the rest of the time.) The decision, she noted, also misdescribed a pseudogene. How can we trust the decision, Lewis wants to know, if the science is wrong?

AND WHAT ABOUT cDNA? Mark Hoofnagle is even more outraged at the scientific ignorance on display at this, the highest court in the land. He has a long list of grievances, and at his Denialism blog says this about the cDNA discussion:

The Supreme Court has decided that since cDNA is artificial (is it really? We make it with enzymes stolen from viruses so viruses make cDNA too right?), cDNAs can be patented. But the exact same information from the mature RNA is in the cDNA! What’s the damn difference? This is like saying you couldn’t patent a recipe on paper, but if you transfer it word for word onto sheepskin, it becomes patentable.

Hoofnagle is just one of a number of bloggers who think the cDNA comments make little sense. It may prove difficult to maintain a distinction between "natural" DNA and cDNA, according to Daniel Fisher at Forbes. He quotes a biochemist-lawyer expressing sadness at the Supremes' lack of biology knowledge. It's not correct, she says, to insist that cDNA is not a product of nature. At Tech Review, Susan Young gives examples of cDNA in nature.

The decision has had one immediate practical effect. At Discover's D-brief, Lisa Raffensperger reports that the price of BRCA testing has dropped by 75%.

JONAH LEHRER STILL WANTS YOUR LOVE. You will have heard, of course, that the formerly esteemed science "journo" Jonah Lehrer has started his long climb back toward respectability by successfully perpetrating the sale of a book proposal. The topic is love. No one has ever denied that Lehrer is a clever writer, so selection of this particular subject can only be intentional irony, what?

It's comical, but no real surprise, that pop-science plagiarist and fabricator Jonah Lehrer appears to have lifted someone else's work for his new book proposal … He is not a smooth writer with a regrettable habit of cutting corners — the cut corners are what make the writing smooth. The smoothness is what plays on the lecture circuit. The bogus product is his only product.

Tom Scocca's Gawker screed quoted above takes off from Daniel Engber's Slate post describing the unoriginal material that dots Lehrer's Love proposal. The proposal was more of the same, Engber reports. "It’s a self-help book disguised as a science book that’s dismissive of self-help books." It also, Engber says, reuses/lifts/massages/absconds with material from an Adam Gopnik piece on marriage. Not at all surprising, really. It's what Lehrer does.

Says Paul Raeburn at the Knight Science Journalism Tracker:

As far as I know, nobody has disclosed what Lehrer was paid. The signing by a major publisher is, in my view, an affront to journalists who have been playing by the rules.

Paul's indignation is a pretty typical comment. Surprise is what John Rennie expresses at his PLoS blog The Gleaming Retort, where he says he and other science writers are flabbergasted by the news that Lehrer has sold his book.

Surprised? Not really. Not surprised. I predicted last year that Lehrer would resurface with a book, and I wasn't alone. It's the venerable and venerated road back for a certain element of the disgraced. Think Richard Nixon. Also, Lehrer is a writer, often quite a skilled one. Of course he will try to return with a book. What else can he do?

In a very long post at SciAm's Literally Psyched, Maria Konnikova comes close to blaming the victims, the credulous readers who have made Lehrer's reputation by buying his books and hanging on his spoken words as well. She argues that the way to deal with Lehrer's misdeeds is to boycott the book when it appears. No interviews. Don't review it. Don't buy it.

No problemo.